Idleguy library

Updating ASAP.

Here are all 50 of the great short novels under 200 pages previously featured

in Idleguy.com issues October, December, 2023, Jananury, February and March, 2024.

The Invention of Morel

by Adolfo Bioy Casares, (1940) : 103 pages

Of Mice and Men

by John Steinbeck, (1937) : 107 pages

Animal Farm

by George Orwell, (1945) : 112 pages

The Hound of the Baskervilles

by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, (1902) : 112 pages

The Postman Always Rings Twice

by James M. Cain, (1933) : 112 pages

Passing

by Nella Larsen, (1929) : 122 pages

The Stranger

The Stranger

by Albert Camus, translated by Matthew Ward, (1942) : 123 pages

For anybody not familiar with the existentialist style of Camus, this is a must read, after which, in case you're still suffering from post-covid blues, "The Plague" is highly recommended. A contemporary of Jean Paul Sartre, Camus' prose leaves one in a state of suspended apprehension, similar to the effect of a work by Franz Kafka. The "Stranger" is quite possibly the greatest book to read in one sitting of all time.

Pedro Paramo

by Juan Rulfo, (1955) : 128 pages

The Cloven Viscount

by Italo Calvino, (1959) : 128 pages

The Awakening

The Awakening

by Kate Chopin, (1899) : 143 pages

The Death of Ivan Ilyich

The Death of Ivan Ilyich

by Leo Tolstoy (1886)

Tolstoy examines the long agony of a man gradually coming to terms with his own mortality.

Vladimir Nabokov described the book thusly, "The Tolstoyan formula is: Ivan lived a bad life and since the bad life is nothing but the death of the soul, then Ivan lived a living death; and since beyond death is God's living light, then Ivan died into a new life: Life with a capital L."

In Watermelon Sugar

In Watermelon Sugar

by Richard Brautigan (1968)

DEATH is a place where the sun shines a different colour every day and where people travel to the length of their dreams. Rejecting the violence and hate of the old gang at the Forgotten Works, they lead gentle lives in watermelon sugar. In this book, Richard Brautigan discovers and expresses the mood of the counterculture generation.

The Autobiography Of An Ex Colored Man

The Autobiography Of An Ex Colored Man

by James Weldon Johnson (1912)

James Weldon Johnson's fictional account of a light-skinned mulatto who can pass for white is the basis for this immersion into race. The anonymous narrator is the son of a black mother and a white father living in the early part of the 20th century in the rural south, the urban north and in Europe. The novel masterfully explores the complexity of race relations between whites and blacks in America and the search for racial identity by one of mixed ethnicity.

Death in Venice

Death in Venice

by Thomas Mann (1912)

Absolutely brilliant tale of things nice people don't talk about. Mann's ability to take a touchy subject and weave a story around it is a masterstroke of imagination and creativity. That the story was written over 100 years ago belies the interpretation of current trends as anything but new.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle

We Have Always Lived in the Castle

by Shirley Jackson (1962)

My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise, I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the death-cap mushroom. Everyone else in my family is dead...

A Single Man

A Single Man

by Christopher Isherwood (1964)

A single day in the life of a middle-aged English expat, a professor living uneasily in California after the unexpected death of his partner.

Notes from Underground

Notes from Underground

by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1864)

Dostoevsky's most revolutionary novel, Notes from Underground marks the dividing line between 19th and 20th century fiction, and between the visions of self each century embodied. One of the most remarkable characters in literature, the unnamed narrator is a former official who has defiantly withdrawn into an underground existence. In complete retreat from society, he scrawls a passionate, obsessive, self-contradictory narrative that serves as a devastating attack on social utopianism and an assertion of man's essentially irrational nature.

Ice

Ice

by Anna Kavan (1967)

A search for an elusive girl in a frozen, seemingly post-nuclear, apocalyptic landscape is the setting for this apocalyptic story. The country has been invaded and is being governed by a secret organization. There is destruction everywhere; great walls of ice overrun the world. Together with the narrator, the reader is swept into a hallucinatory quest for this strange and fragile creature with albino hair. Acclaimed upon its 1967 publication as the best science fiction book of the year, this extraordinary and innovative novel has subsequently been recognized as a major work of literature in its own right.

Cane

Cane

by Jean Toomer (1923)

An innovative literary work that is part drama, part poetry, part fiction, powerfully evokes black life in the American South. Rich in imagery, Toomer's impressionistic, sometimes surrealistic sketches of Southern rural and urban life are permeated by visions of smoke, sugarcane, dusk, and fire.

The Drowned World

The Drowned World

by J.G. Ballard (1962)

A forerunner of the current climate change (previously, Global Warming) insanity, Ballard has the world in the 21st century affected by fluctuations in solar radiation have caused the ice-caps to melt and the seas to rise. Civilization has retreated to the Arctic and Antarctic circles. London is a city now inundated by a primeval swamp, to which an expedition travels to record the flora and fauna of this new Triassic Age.

Hunger

Hunger

by Knut Hamsun (1890)

One of the most important and controversial writers of the 20th century, Knut Hamsun made literary history with the publication in 1890 of this powerful, autobiographical novel recounting the abject poverty, hunger and despair of a young writer struggling to achieve self-discovery and its ultimate artistic expression. The book brilliantly probes the psychodynamics of alienation, obsession, and self-destruction, painting an unforgettable portrait of a man driven by forces beyond his control to the edge of the abyss. Hamsun influenced many of the major 20th-century writers who followed him, including Kafka, Joyce and Henry Miller. Required reading in world literature courses, the highly influential, landmark novel will also find a wide audience among lovers of books that probe the "unexplored crannies in the human soul" (George Egerton).

Giovanni's Room

Giovanni's Room

by James Baldwin (1956)

Baldwin's haunting and controversial second novel is his most sustained treatment of sexuality. In a 1950s Paris swarming with expatriates and characterized by dangerous liaisons and hidden violence, an American finds himself unable to repress his impulses. Examining the mystery of love and passion in an intensely imagined narrative, Baldwin creates a moving and complex story of death and desire that is revelatory in its insight.

O Pioneers!

O Pioneers!

by Willa Cather (1913)

O Pioneers! was Willa Cather's first great novel, and to many it remains her unchallenged masterpiece. No other work of fiction so faithfully conveys both the sharp physical realities and the mythic sweep of the transformation of the American frontier - and the transformation of the people who settled it. At once a sophisticated pastoral and a prototype for later feminist novels, O Pioneers! is a work in which triumph is inextricably enmeshed with tragedy, a story of people who do not claim a land so much as they submit to it and, in the process, become greater than they were.

Bonjour Tristesse

Bonjour Tristesse

by Francoise Sagan (1955)

Published when she was only nineteen, Francoise Sagan's astonishing first novel Bonjour Tristesse became an instant bestseller. It tells the story of Cecile, who leads a carefree life with her widowed father and his young mistresses until, one hot summer on the Riviera, he decides to remarry - with devastating consequences. In A Certain Smile, Dominique, a young woman bored with her lover, begins an encounter with an older man that unfolds in unexpected and troubling ways. These two acerbically witty and delightfully amoral tales about the nature of love are shimmering masterpieces of cool-headed, brilliant observation.

Billy Budd, Sailor

Billy Budd, Sailor

by Herman Melville (1924)

A handsome young sailor is unjustly accused of plotting mutiny in this timeless tale of the sea, penned by the undisputed master of the oceanic tale.

The Crying of Lot 49

The Crying of Lot 49

by Thomas Pynchon (1966)

The shortest of Pynchon's novels, the plot follows Oedipa Maas, a young Californian woman who begins to embrace a conspiracy theory as she possibly unearths a centuries-old feud between two mail distribution companies. Like most of Pynchon's writing, suffused with rich satire, chaotic brilliance, verbal turbulence and wild humor, The Crying of Lot 49 is often described as postmodernist literature.

The Trial

The Trial

by Franz Kafka (1925)

Written in 1914 but not published until 1925, a year after Kafka's death, The Trial is the terrifying tale of Josef K., a respectable bank officer who is suddenly and inexplicably arrested and must defend himself against a charge about which he can get no information. A prophecy of the excesses of modern bureaucracy wedded to the madness of totalitarianism, The Trial is a classic in the pantheon of existential literature which goes well with Merlot, LSD, and George Orwell's 1984.

A Personal Matter

A Personal Matter

by Kenzaburo Oe (1968)

Kenzaburo Oe, the winner of the 1994 Nobel Prize for Literature, is internationally acclaimed as one of the most important and influential post-World War II writers, known for his powerful accounts of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and his own struggle to come to terms with a mentally handicapped son. The Swedish Academy lauded Oe for his "poetic force [that] creates an imagined world where life and myth condense to form a disconcerting picture of the human predicament today."

Nightwood

Nightwood

by Djuna Barnes (1936)

Full of obscenely misfit characters, this disturbing novella trends towards modernist sub-realities as one of the first books of the 20th century to explicitly portray a lesbian relationship. Get from it what you can, because it is a fleeting insight.

Snow Country

Snow Country

by Yasunari Kawabata (1937)

Nobel Prize recipient Yasunari Kawabata's Snow Country is widely considered to be the writer's masterpiece, a powerful tale of wasted love set amid the desolate beauty of western Japan. In chronicling the course of a doomed romance, Kawabata has created a story for the ages, a stunning novel dense in implication and exalting in its sadness.

Wide Sargasso Sea

Wide Sargasso Sea

by Jean Rhys (1966)

With Wide Sargasso Sea, her last and best-selling novel, Jean Rhys ingeniously brings into light one of fiction's most fascinating characters: the madwoman in the attic from Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre. This mesmerizing work introduces us to Antoinette Cosway, a sensual and protected young woman who is sold into marriage to the prideful Mr. Rochester. Rhys portrays Cosway amidst a society so driven by hatred, so skewed in its sexual relations, that it literally drives a woman out of her mind.

Silas Marner

Silas Marner

by George Eliot (1861)

Silas Marner, a weaver in the slum of Lantern Yard, stands falsely accused of stealing funds from his small Calvinist congregation. His life in tatters, Silas flees south and settles near the village of Ravenloe, only to have his life disrupted again when a local scoundrel, Dunsey Cass, steals his small fortune. It is only after becoming the guardian of an orphaned child that Silas's luck begins to change as he is transformed from an embittered man into one capable of love and forgiveness, with the means for spiritual rebirth and redemption from his ruinous past. In Silas Marner George Eliot subtly critiques the impacts of industrialization, the role of the upper class and the function of organized religion. The work has been adapted many times, most notably by the BBC with Ben Kingsley portraying Silas Marner.

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie

by Muriel Spark (1961)

The brevity of Muriel Spark's novels is equaled only by their brilliance. These four novels, each a miniature masterpiece, illustrate her development over four decades. Despite the seriousness of their themes, all four are fantastic comedies of manners, bristling with wit. Spark's most celebrated novel, THE PRIME OF MISS JEAN BRODIE, tells the story of a charismatic schoolt The brevity of Muriel Spark's novels is equaled only by their brilliance. These four novels, each a miniature masterpiece, illustrate her development over four decades. Despite the seriousness of their themes, all four are fantastic comedies of manners, bristling with wit. Spark's most celebrated novel, THE PRIME OF MISS JEAN BRODIE, tells the story of a charismatic schoolteacher's catastrophic effect on her pupils. THE GIRLS OF SLENDER MEANS is a beautifully drawn portrait of young women living in a hostel in London in the giddy postwar days of 1945. THE DRIVER'S SEAT follows the final haunted hours of a woman descending into madness. And THE ONLY PROBLEM is a witty fable about suffering that brings the Book of Job to bear on contemporary terrorism. Characters are vividly etched in a few words; earth-shaking events are lightly touched on. Yet underneath the glittering surface there is an obsessive probing of metaphysical questions: the meaning of good and evil, the need for salvation, the search for significance

Jakob von Gunten

Jakob von Gunten

by Robert Walser (1969)

The Swiss writer Robert Walser is one of the quiet geniuses of twentieth-century literature. Largely self-taught and altogether indifferent to worldly success, Walser wrote a range of short stories, essays and four novels, of which Jakob von Gunten is widely recognized as the finest. It tells the story of a seventeen-year-old runaway from an old family who enrolls in a school for servants. The Institute, run by the domineering Herr Benjamenta and his beautiful but ailing sister, is a deeply mysterious place: the faculty lies asleep in a single room. The students though subject to fierce discipline, come and go at will. Jakob, an irrepressibly subversive presence, keeps a journal in which he records his quirky impressions of the school as well as his own quickly changing enthusiasms and uncertainties, deliberations and dreams. And in the end, as the Institute itself dissolves around him like a dream, he steps out boldly to explore still-unimagined worlds.

Breakfast at Tiffany's

Breakfast at Tiffany's

by Truman Capote (1958)

It's New York in the 1940s, where the martinis flow from cocktail hour till breakfast at Tiffany's. And nice girls don't, except, of course, Holly Golightly. Pursued by Mafia gangsters and playboy millionaires, Holly is a fragile eyeful of tawny hair and turned-up nose, a heart-breaker, a perplexer, a traveller, a tease. She is irrepressibly 'top banana in the shock department', and one of the shining flowers of American fiction. This edition also contains three stories: 'House of Flowers', 'A Diamond Guitar' and 'A Christmas Memory'.

Things Fall Apart

Things Fall Apart

by Chinua Achebe (1958)

Things Fall Apart tells two intertwining stories, both centering on Okonkwo, a "strong man" of an Ibo village in Nigeria. The first, a powerful fable of the immemorial conflict between the individual and society, traces Okonkwo's fall from grace with the tribal world. The second, as modern as the first is ancient, concerns the clash of cultures and the destruction of Okonkwo's world with the arrival of aggressive European missionaries. These perfectly harmonized twin dramas are informed by an awareness capable of encompassing at once the life of nature, human history, and the mysterious compulsions of the soul. From the Trade Paperback edition.

Fat City

Fat City

by Leonard Gardner (1969)

Fat City is a novel about the indestructibility of of hope, the anguish and comedy of the human condition. It tells the story of two young boxers out of Stockton, California: Ernie Munger and Billy Tully, one in his late teens, the other just turning thirty, whose seemingly parallel lives intersect for a time. Set in an ambiance of glittering dreams and drab realities, it tells of the two fighters' struggles to escape the confinements of their existence, and of the men and women in their world. Fat City is a novel about the sporting life like no other ever written: without melodrama or false heroics, written with a truthfulness that is at once painful and beautiful.

House Made of Dawn

House Made of Dawn

by N. Scott Momaday (1968)

The magnificent Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of a stranger in his native land A young Native American, Abel has come home from a foreign war to find himself caught between two worlds. The first is the world of his father's, wedding him to the rhythm of the seasons, the harsh beauty of the land, and the ancient rites and traditions of his people. But the other world — modern, industrial America — pulls at Abel, demanding his loyalty, claiming his soul, goading him into a destructive, compulsive cycle of dissipation and disgust. And the young man, torn in two, descends into hell.

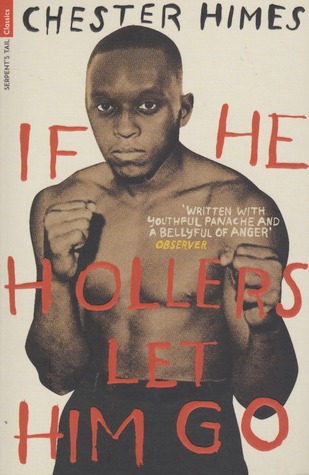

If He Hollers Let Him Go

If He Hollers Let Him Go

by Chester Himes (1945)

Robert Jones has a lot going for him: a steady job, a steady relationship and plenty of prospects, despite his constant struggle for survival as a back man in a white man's world. If He Hollers Let Him Go follows four days oh Jones' life, culminating in a devestating accusation that threatens every element of Jones' precarious existence. Immediately recognised as a masterful expose of racism in everyday life, If He Hollers Let Him Go is Chester Himes' first book, originally published in 1945 to great acclaim.

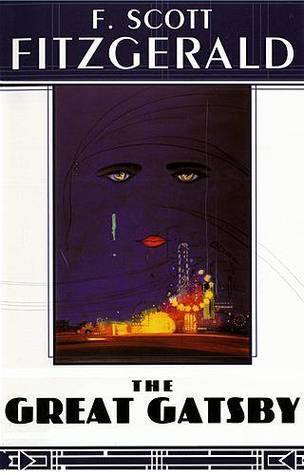

The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby

by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925)

The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald's third book, stands as the supreme achievement of his career. This exemplary novel of the Jazz Age has been acclaimed by generations of readers. The story is of the fabulously wealthy Jay Gatsby and his new love for the beautiful Daisy Buchanan, of lavish parties on Long Island at a time when The New York Times noted "gin was the national drink and sex the national obsession," it is an exquisitely crafted tale of America in the 1920s. The Great Gatsby is one of the great classics of twentieth-century literature. (back cover)

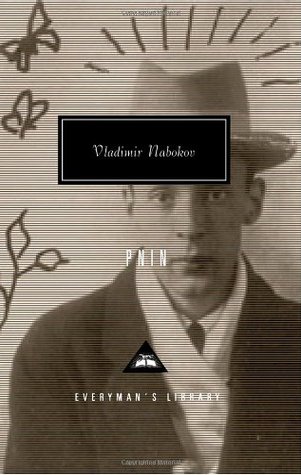

Pnin

Pnin

by Vladimir Nabokov (1957)

One of the best-loved of Nabokov's novels, Pnin features his funniest and most heart-rending character, professor Timofey Pnin. A haplessly disoriented Russian emigre precariously employed on an American college campus in the 1950s, Pnin struggles to maintain his dignity through a series of comic and sad misunderstandings, all the while falling victim both to subtle academic conspiracies and to the manipulations of a deliberately unreliable narrator. Initially an almost grotesquely comic figure, Pnin gradually grows in stature by contrast with those who laugh at him. Whether taking the wrong train to deliver a lecture in a language he has not mastered or throwing a faculty party during which he learns he is losing his job, the gently preposterous hero of this enchanting novel evokes the reader's deepest protective instinct. Serialized in The New Yorker and published in book form in 1957, Pnin brought Nabokov both his first National Book Award nomination and hitherto unprecedented popularity.

Norwood

Norwood

by Charles Portis (1966)

Ex-Marine Norwood Pratt of Ralph, Texas, accepts an offer to deliver a car to New York and takes the Trailways bus back to Texas. The story is told in the language of the rural South, in conversation that sounds like Country Western music.

Ubik

Ubik

by Philippe K. Dick (1969)

Ubik is Dick's masterpiece, filled with psychics, dead wives partially saved in cold storage, and disruptions to time and reality that can be remediated by an aerosol available at the local drugstore. If it wasn't part of this world, it would be out of it.

Near to the Wild Heart

Near to the Wild Heart

by Clarice Lispector (1943)

Clarice Lispector's first novel, Near to the Wild Heart was written from March to November 1942 and published around her twenty-third birthday. Written in a stream-of-consciousness style reminiscent of the English-language Modernists, the story centers around the childhood and early adulthood of a character named Joana, who bears strong resemblance to her author. The book, particularly its revolutionary language, brought its young, unknown creator to great prominence in Brazilian letters and earned her the prestigious Graca Aranha Prize. Joana, a young woman very much in the mode of existential contemporaries like Camus and Sartre, ponders the meaning of life, the freedom to be one's self, and the purpose of existence.

A Clockwork Orange

A Clockwork Orange

by Anthony Burgess (1962)

A vicious fifteen-year-old droog is the central character of this 1963 classic. In Anthony Burgess's nightmare vision of the future, where criminals take over after dark, the story is told by the central character, Alex, who talks in a brutal invented slang that brilliantly renders his and his friends' social pathology. A Clockwork Orange is a frightening fable about good and evil, and the meaning of human freedom. And when the state undertakes to reform Alex to redeem him, the novel asks, "At what cost?" This edition includes many notes, a NADSAT Glossary, and some essays, articles, and reviews.

Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead

Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead

by Barbara Comyns (1954)

This is the story of the Willoweed family and the English village in which they live. It begins mid-flood, ducks swimming in the drawing-room windows as they sail around the room. A series of gruesome deaths plagues the villagers. Through all madeness, Comyns' unique voice weaves a narrative as wonderful as it is horrible, as beautiful as it is cruel. Originally published in England in 1954, this overlooked, small masterpiece is a twisted, tragicomic gem.

Their Eyes Were Watching God

Their Eyes Were Watching God

by Zora Neale Hurston (1937)

Fair and long-legged, independent and articulate, Janie Crawford sets out to be her own person - no mean feat for a black woman in the 1930s. Janie's quest for identity takes her through three marriages and a journey back to her roots.

Ethan Frome

Ethan Frome

by Edith Wharton (1911)

Ethan Frome is haunted by a past of lost possibilities until his wife's orphaned cousin, Mattie Silver, arrives and he is tempted to make one final, desperate effort to escape his fate. In language that is spare, passionate, and enduring, Edith Wharton tells this unforgettable story of two tragic lovers overwhelmed by the unrelenting forces of conscience and necessity.Included with Ethan Frome are the novella The Touchstone and three short stories. Together, this collection offers a survey of the extraordinary range and power of one of America's finest writers.

Picnic at Hanging Rock

Picnic at Hanging Rock

by Joan Lindsay (1967)

It was a cloudless summer day in the year nineteen hundred. Everyone at Appleyard College for Young Ladies agreed it was just right for a picnic at Hanging Rock. After lunch, a group of three of the girls climbed into the blaze of the afternoon sun, pressing on through the scrub into the shadows of Hanging Rock. Further, higher, till at last they disappeared. They never returned. Whether Picnic at Hanging Rock is fact or fiction the reader must decide for themselves.

The Magic Toyshop

The Magic Toyshop

by Angela Carter (1967)

One night Melanie walks through the garden in her mother's wedding dress. The next morning her world is shattered. Forced to leave the comfortable home of her childhood, she is sent to London to live with relatives she never met. The classic gothic novel established Angela Carter as a most imaginative writer and augurs the themes of her later creative works.

The Stranger

The Stranger